A Night at the Gay Sauna: Where Desire Comes Out

It is Friday night. Down one alley of a busy shopping and entertainment district of Seoul, young men move through what appear to be closed doors of a dilapidated building. A slow trickle of customers — some dressed in suits, others as hipsters — enter the inconspicuous establishment, seeking to

Inside One of South Korea's So-Called Global Firms

From Wikipedia I have been the sole foreign employee at a vaunted South Korean technology firm for about 15 months. Given my company’s fame, people often want to know what that’s like and at times the simplest answer I can give them is this: It’s been as

Park Geun-hye's Presidency Is Adrift

The Korean version of this essay can be found here. Embed from Getty Imageswindow.gie=window.gie||function(c){(gie.q=gie.q||[]).push(c)};gie(function(){gie.widgets.load({id:'By5htD2XTEVQ74947taqxg',sig:'B6i1ljR8hTbDQ62tiEYzabkgfCQbMzPsiDyxHZVCaHg=',w:'594px',h:'388px',items:'450148594',caption: true ,tld:'com',is360: false })}); Park Geun-Hye has

How I Became an Ajumma

The Korean version of this essay appeared in the Kyunghyang Shinmun on 12 February 2015. The English version here has been published with the permission of the newspaper and the author. I have lived in many countries, but the ajumma character seems rather unique to South Korea. In case

The End of South Korea's Rural Schools

Every Wednesday I teach at what must be one of the smallest public schools in South Korea: Anpyeong Middle School, home to just seven students. Seven students. That’s two 7th graders, three 8th graders, and two 9th graders. The school is set to close next year. Its closing represents

Salt Flowers: Glimpses of South Korea’s Labour Landscape

Sweat stains on an old pair of overalls, or sweat stains on a fine shirt. South Koreans call them both “salt flowers”: beautiful traces of hard labour. It is a symbol of labour’s immeasurable value, beyond the understanding of those who never work and sweat. Calling a sweat stain

Memories of Dictatorship from Not Long Ago

One night in 1972, I was having dinner with an American friend and her fiancé at the restaurant of the YMCA in downtown Seoul. It was a dangerous time. The talk of the town was a constitutional change the government was pushing for so that then-President Park Chung-hee

Men Who Yearn to Be Erect, and the Women Who Bear Them

He leans in and caresses her face. He plants his lips on hers. She opens her eyes wide, looking utterly surprised. Then she gives in, chastely closing her eyes as she keeps herself perfectly still. When I get around to watching a South Korean drama, this is more or less

South Korea's Real Culture of Shame

Academic literature has extensively documented the so-called ‘culture of shame’ in East Asia, and South Korea is no exception to the phenomenon as a national collective that suffers acutely from fear of losing one’s face — chemyeon as they say in Korean. Shame over possible loss of one’s

When the Elite Don't Care

K.R.K. for Korea Exposé If Park Geun-hye chooses you for prime minister, beware because your political career is in peril. That is the joke in South Korean cyberspace where the biggest topic is the nomination of Lee Wan-koo, former floor leader of the ruling Saenuri Party, as

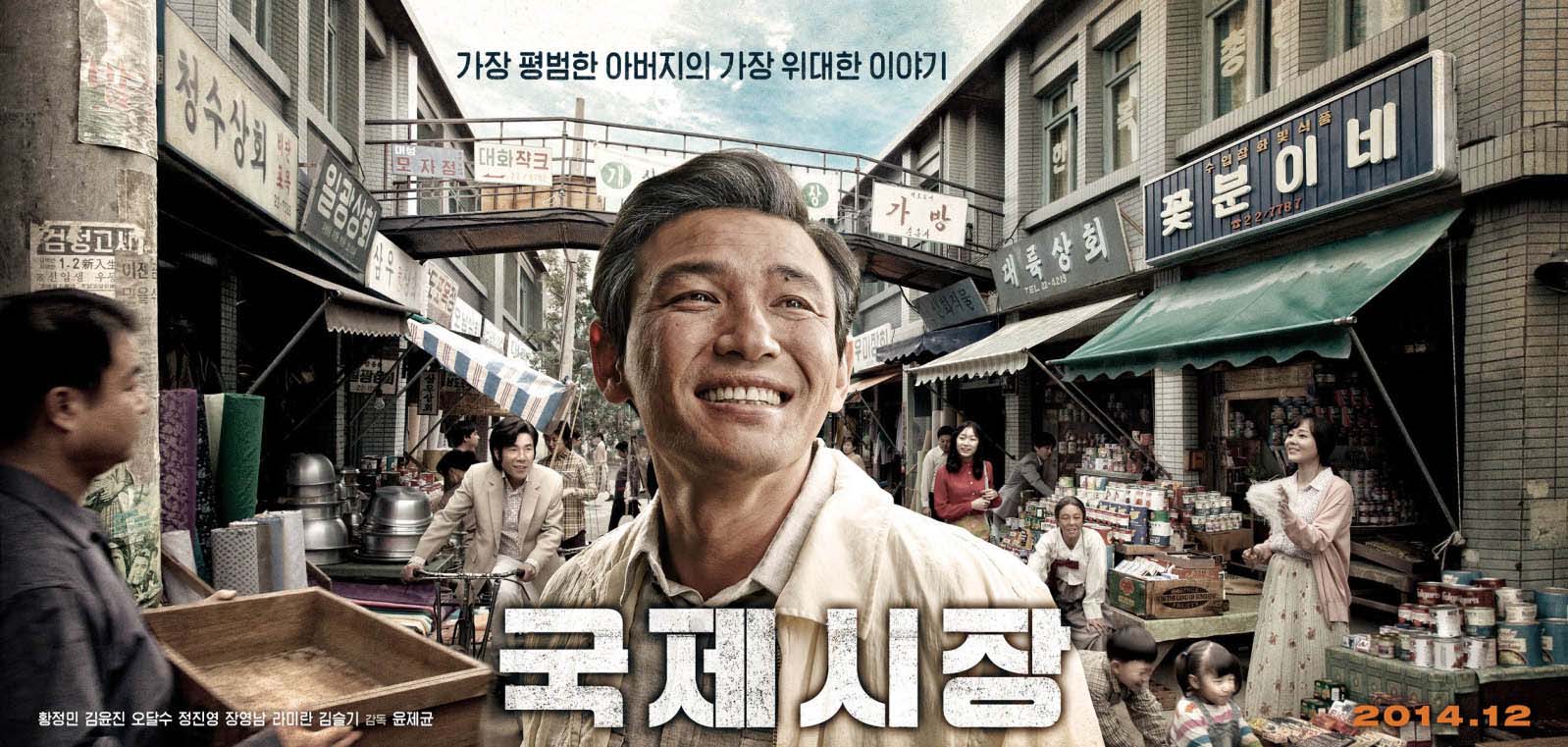

History Guides the Future in South Korea's Latest Blockbuster

Three uniformed South Korean high school students mercilessly heckle a South Asian migrant laborer in contemporary Busan. Seeing this, an elderly Korean man flies into a rage against them. The privileged youngsters are oblivious to the fact that the old man, Deok-soo, had himself been a migrant laborer. In fact,

A Nation as Beautiful as a Rolex Knockoff

I only recently saw the photos of 20 remarkably identical-looking Miss Korea contestants. The shots of these polished young women inspire both horror and confusion. They look like they were made from the same cookie cutter, mass-produced at some beauty queen factory, like the same model iPhones in a Chinese